Teaching patent drafting in Africa - September 2007:

Awakening to my first morning in Africa, I throw open the curtains to a view of the towering headquarters of Robert Mugabe's ruling party, Zanu-PF, just a few hundred meters away. I look back across my hotel room at my garment bag; it's all I have. With my suitcase lost in transit either in London or in Johannesburg, I did not yet realize that I cannot easily replace even the most basic necessities, such as my razor and belt. The national economy has mostly collapsed, and the shelves of the stores that remain open are mostly empty. For many items, the "black market" is now the only viable source; and many staples (including petrol) simply are no longer publicly available--at any price. Left to my own resources, I slice up a black sock and fabricate a belt from it to hold up my trousers.

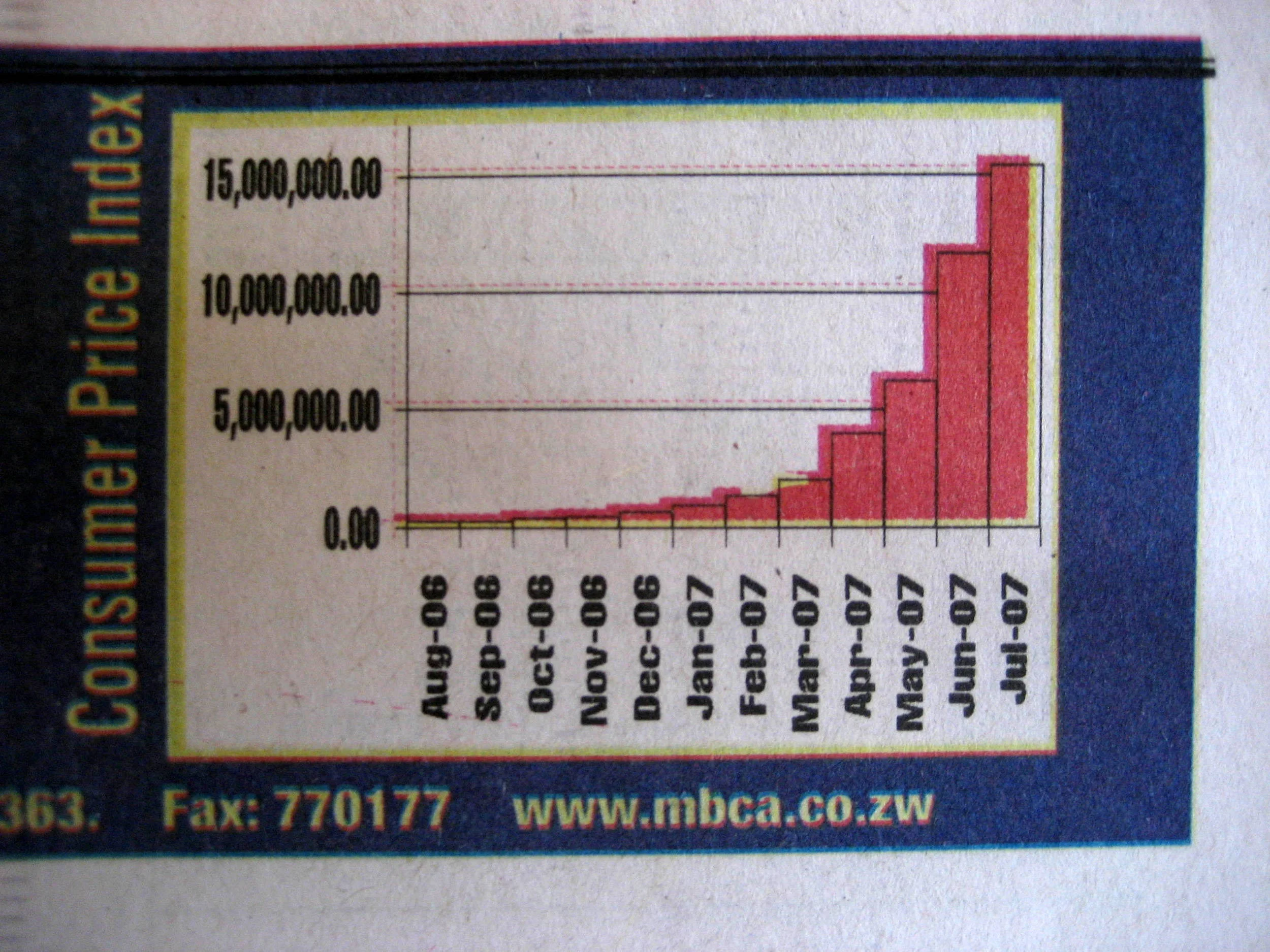

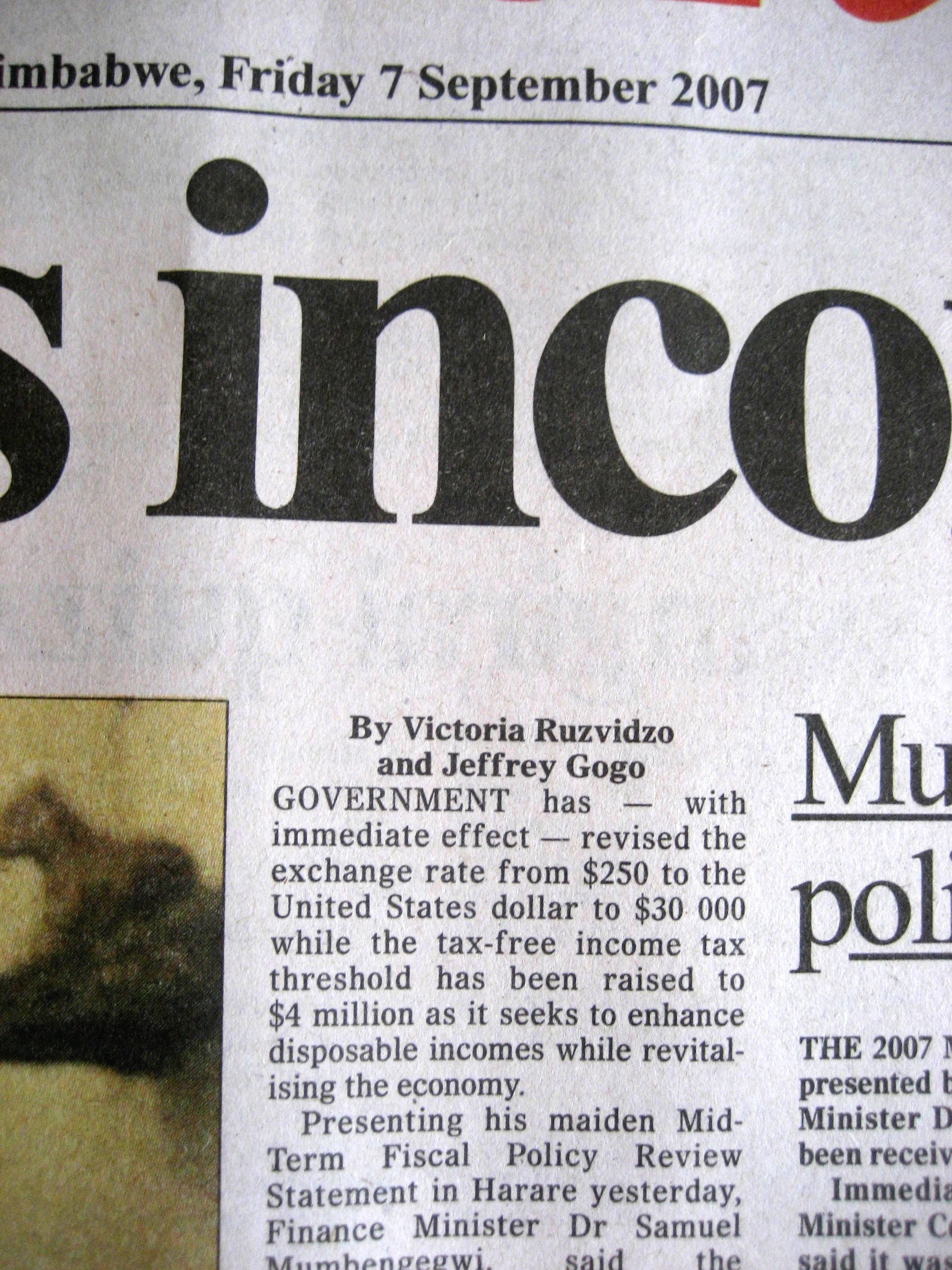

I open my door and look down at the city newspaper, The Herald. The lead story opens, "Government has--with immediate effect--revised the exchange rate from $250 to the United States dollar to $30 000 . . . " Yes, the official currency exchange rate has changed by a factor of over 100 in the less-than-24-hours that I have been in this country. It's a completely different world from the one I left when I departed big-firm practice a month earlier. Welcome to Zimbabwe.

In spite of the challenges in Zimbabwe today--a country that has reportedly seen about a quarter of its population evacuate, mostly to South Africa, in just this calendar year--my visit profoundly changed my perception of Africa, provided me with a perspective on the role and potential of patent law and patent drafters that I had never imagined, and gave me an opportunity to help set the foundations for the long-term economic advancement of Africa.

Of course, I also quickly recognized that my struggles were trivial compared with those faced by Zimbabweans, who persevered through it all with remarkable resourcefulness, dignity, and grace. The residents of Zimbabwe, despite their struggles, were uniformly warm and welcoming. Venturing across the city and meeting people on the streets, we never once were threatened or otherwise made to feel unsafe. The folks from the African Regional Intellectual Property Office (ARIPO) were magnificent hosts; they all were incredibly hard-working, and they consistently made extraordinary efforts to satisfy our needs and wants and to make our visit thoroughly enjoyable, despite the challenges, each and every day. Moreover, we were treated with the wonderfully enriching experience of spending many hours with ARIPO officials, including the very cordial Director General (to whom everyone refers simply as "D.G."), collegially exchanging perspectives on patent law and policy as well as other global issues.

The participants--from Zimbabwe, South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Mauritius, Ghana, Zambia, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Mozambique--exhibited extraordinary commitment, dedication, and enthusiasm for learning patent drafting. Their passion was palpable, as they clearly grasped the potential that patenting could hold for their countries in terms of capitalizing on their innovation and competing on the world stage; and they recognized that they could be among the pioneers in Africa who could make that happen. They acted as though they were carrying the hopes of their countries on their shoulders; and, in a very real sense, they may be.

Innovation abounds from the many brilliant scientists and engineers in Zimbabwe and in other African member states. After my first morning awakening in Zimbabwe, we visited the Scientific & Industrial Research & Development Centre (SIRDC) in Harare. I was amazed by the breadth and sophistication of their work in domains such as construction materials, agriculture, biotechnology, and alternative energy. Already, solar-powered traffic lights developed by SIRDC can be found across Harare. While at SIRDC, we were given a lab tour by a researcher developing new varieties of drought-tolerant maize through the use of molecular marker-assisted selection. Although the lab was filled with advanced equipment for genetic analysis, the most critical piece of equipment likely was the uninterruptable power supply, which kicked in during our visit, as the SIRDC lost power from the grid due to one of Harare's frequent blackouts. I was stunned to see how the scientists appeared to be so unphased by challenges, such as the absence of a dependable power supply, while pushing forward with their work. SIRDC has only recently begun filing patent applications; though, with a new director who holds dozens of patents, the mindset of SIRDC is rapidly evolving, raising the likelihood that their patent filings will increase dramatically in the years to come. Observing the very impressive innovation at SIRDC made me realize how truly "flat" the world is becoming.

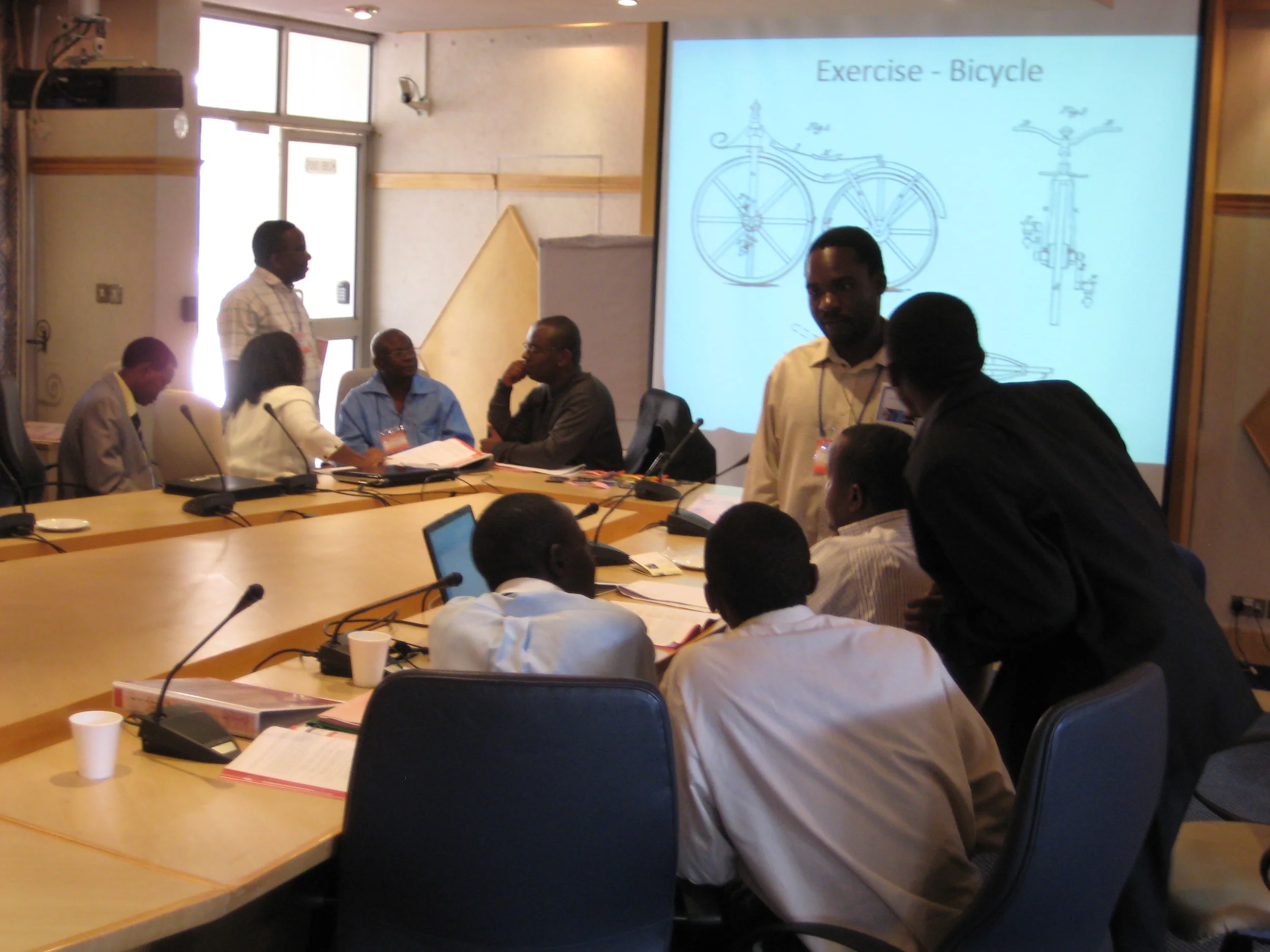

By any measure, all agreed that the patent drafting training program--the first of its kind for ARIPO members and neighboring states--was a landmark success. I was paired with Naveen Modi, a genuine team player and a superb instructor from the DC office of Finnegan Henderson, in teaching the second week of the program. Following a first week consisting mostly of prepared lectures, we mostly led group claim-drafting exercises. In the early exercises, we observed common mistakes, such as failing to properly establish antecedent basis for claim elements and improperly formatting dependent patent claims. Remarkably, though, we needed to offer corrective guidance only once, as they so readily absorbed our feedback and would not make the same mistakes again. Within a few days, my feedback was mostly limited to non-corrective questions probing their train of thought in selecting and characterizing claim elements.

As the students were so keen to learn, we began on Tuesday to distribute invention disclosures at the end of the day, asking that they review the disclosures overnight and be ready to draft claims in groups the following morning. The following morning I was dumbstruck to see how many of the participants arrived (always early) with pages and pages of claims of different types/scope/styles, etc., that they drafted the night before on their own volition. They were just so eager to practice what they had learned, and their enthusiasm was both contagious and inspiring. The participants also were full of pertinent questions and insightful comments, which they shared freely in class, creating a very interactive and dynamic learning experience for all.

For our final exercise on Friday, we gave each participant a multi-use pen that included a stylus, a laser pointer, and a flashlight; and we asked each of them to draft a claim to it and read it to the group. A solid claim resulted in a "pass." Each and every one of them drafted a solid claim, and many were highly imaginative. As they left the program, they all seemed so eager to continue with their studies and to further progress as patent drafters.

Finally, the coordinators from the World Intellectual Property Office, Francoise Wege, and Yumiko Hamano both were wonderfully fun; and it was very rewarding to receive their approval of our work. The program provided me with one of the most rewarding experiences I have had as a patent attorney, as I believe that many of the participants will carry on, share what they have learned, and significantly advance efforts to address the critical need for skilled patent drafters so that research institutions and other entities in Africa can begin to file patent applications at a rate that is much higher and more commensurate with the high level of innovation that I observed.

![Here, I meet an ~300-year-old galapagos tortoise [Geochelane elephontopus (Kamba)]--not sure quite how he found his way to Zimbabwe.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56103d02e4b0edf3da1e7280/1445956864501-IO9J8Z23XB63JNU4RH7Z/IMG_0656.JPG)